A Game to Serve the Setting

Part I: A World Where Everyone Gets to be Conan

In “d&d is anti-medieval,” Paul over at Blog of Holding argues that Original D&D from 1974 does not represent a medieval, European society on either a fundamental or a superficial level.

Unlike a medieval or even a capitalist society, the bulk of the land is free and unclaimed. You can wander the wilderness killing monsters and looting tombs without attracting the concern of a nobility that might fear violent and wealthy peasants.

Paul refers to the setting as both social-classless and stateless, but “classless” would properly describe a setting without wealth disparity. OD&D is merely stateless, an anarchist or libertarian society absent modern technology.

Paul concludes that this unique social model is “an American fantasy of empowerment and upward mobility,” either a subconscious or deliberate attempt by Gary Gygax to give his fantasy a Wild West or “New World spin.”

I’d like to propose a more concrete explanation.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that OD&D is not dominated by the trappings of medieval Western Europe. Its main influence was the Sword & Sorcery genre of fantasy, in which prehistoric, ancient, and even far-future societies often find themselves side-by-side with medieval kingdoms.

Let’s take Conan the Barbarian as the ur-example of Sword & Sorcery, and therefore the ur-influence on OD&D. Much has been said about Conan’s roots in both the Western genre and Robert E. Howard’s upbringing in Texas, so it is natural that OD&D should evoke the “American fantasy” which Paul suggests.

That said, Howard’s Hyboria is not a stateless setting. Conan can rely on his intimidating frame to keep the law away for a time, but sooner or later he has to skip town and move on to the setting of another story.

Furthermore, the thought of Conan simply buying a castle strikes one as rather silly. What sort of barbarian buys his way into luxury without a good fight? Conan is never out to actually spend any stolen treasure; he steals for the glory of accomplishing something no one else has.

|

| A rendering of OD&D’s default overworld, original source unknown |

So, why does OD&D take place in a stateless society where land is free?

Well, a campaign where the players are constantly running from the law, with little to no reward but “glory,” sounds fairly exhausting.

The DM can’t settle into running a well-detailed little town and a megadungeon if the king’s men are on the march to arrest the adventurers. “Run around until, one morning, you feel like conquering Aquilonia” is not a compelling arc for players compared to “amass loot until you can afford a stronghold.”

So, the inconveniences of the state and land claims are brushed aside. The world bends to accommodate the fantasy of being Conan, absent any of the hardships of being Conan.

The setting bends to serve the game.

Part II: The Odd vs. the GLOG

|

| Introduction to Bastionland |

I have been thinking a lot about Chris McDowall’s recent post, “A Setting to Serve the Game.” Chris has a knack for inventing strong little design mantras like this one, and I can’t quite say I disagree with his point.

Chris’s post refers mostly to wargaming, but his Electric Bastionland is an excellent example of this principle in RPGs. The setting serves the OD&D-like game using the same fundamental conceit—a stateless society—but it makes a stronger effort to justify that conceit with a heavy dose of dream-logic: Bastion is so overrun by ineffective bureaucracy that no one is really in charge.

But the problem with dream-logic is that, if you stop to try to make any sense of it, you wake up. Immersion is broken.

|

One of the principal influences on my nobility-based mini-RPG, Squires Errant, was “Death, Taxes, and Death Taxes” (pictured above) by Skerples on Coins and Scrolls.

Skerples—partly in response, if I recall correctly, to “d&d is anti-medieval”—set out to run D&D (or, rather, Many Rats on Sticks) in a proper feudal setting. Players must negotiate with noble patrons to loot and profit from a dungeon; one’s Estate (First, Second, or Third) makes a significant difference in how one interacts with the world.

The results, at least in writing, are far too complicated for my tastes, but I find them uniquely inspiring. Whereas the evocative, early twentieth-century details of Electric Bastionland are only skin-deep, the setting of Many Rats on Sticks transforms the structure of play itself.

The game bends to serve the setting.

Part III: The Aesthetic Component of Game Design

|

| Me and my favorite horse in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild |

How did the queen become the most powerful piece in chess? Was it merely a stroke of good game design, an interesting way to differentiate it from the king? Or, as some historians have suggested, was it inspired by this or that powerful queen coming to prominence in the real world?

Let’s take another example. It would seem the setting of Breath of the Wild serves the game. The world is post-apocalyptic—stateless—to give a sense of freedom and exploration. The guardians, integral to the game’s backstory, were designed first and foremost to be obvious and intimidating obstacles, meant to discourage new players from heading straight to the final boss fight.

But, from another angle, the game was designed to serve the setting Zelda players were clamoring for: the world of adventure and free exploration promised by the original Legend of Zelda from 1986. Nintendo threw out the linear structure established by A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time and designed their first open-world game to serve that fantasy.

The standard fantasy setting may have emerged to serve D&D’s mechanics, but the mechanics also emerged to serve the fantasy of being Conan.

|

| a setting to serve the game to serve the setting to serve the game to serve... |

A game, I would propose, is a complex relationship between mechanical and aesthetic elements. Without rules, a chess set is an abstract diorama; with a rulebook and no pieces, you have no a game at all. The process of game design, in my experience, is a constant back-and-forth between mechanical and aesthetic considerations.

The threat of death is a mechanical consequence in old-school RPGs, but it is also an aesthetic, narrative element. The latter didn’t work for the games Dreaming Dragonslayer runs for children, so he removed death. The mechanics changed to serve aesthetic concerns.

Likewise, stateless settings have a tendency to break my willing suspension of disbelief. So, I bent Squires Errant to serve a mildly realistic feudal society. Inspired by Electric Bastionland’s starting debt, I decided you don’t get to keep your treasure at first—your liege does. You can’t just build a castle anywhere, you have to be granted land after you are knighted.

You can carry a weapon openly because you, yourself, are part of the state. There’s no need for a price sheet or detailed tracking of currency: as nobility, you can walk into a shop and take whatever you want for free, provided you aren’t so greedy you anger the commoners.

|

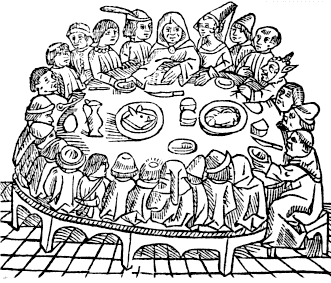

| The Canterbury Tales illustration I use for Squires Errant |

As part of the OSR or DIY-RPG movement or whatever you want to call it, we work on heavily trodden ground. If all the setting can do is serve the game, we’ll end up reproducing the same game over and over again. Already, countless TTRPGs and videogames kill off billions of fictional people in an apocalyptic event just to serve a game about wandering the world, killing people, and stealing treasure without any consequences—being Conan absent any of the hardships of being Conan.

If we consider our games holistically—if we allow the games’ mechanics themselves to change to serve new and, dare I say, more true-to-life settings—we open ourselves up to discovering something new.

Joesky Tax

Here’s a snippet of lore you can steal—I wrote it as an experiment in “setting to serve the game,” particularly to justify the original D&D setting.

At the height of their power, the good kings, wise wizards, and pious patriarchs of the land forged the RULING RINGS to sustain their lives forever.

Now, the rings have drained the land of Law, and the rulers, sequestered in their isolated strongholds, turn their backs on a world overrun by Chaos.

It is left to adventurous inhabitants of the few remaining villages to reclaim the Ruling Rings, and restore civilization to a monster-infested wilderness...

You can knock the Lord of the Rings cliché all you want, but magic rings make a good, tangible source of immortality. I might take some of the ideas here and expand them into an original setting, something of a Chaotic counterpart to the Lawful setting I’m spinning up for Squires.

.jpg)

"The suggestion that every adventure be bookended by this many negotiations is ludicrous and I can’t believe Skerples actually ran it."

ReplyDeleteThe negotiations tend to be relatively short. The PCs are often flush with extra cash and, fearful of thieves and the prospect of imminent death, prefer to pour that cash into the Bank of Feudal Obligation. Few nobles would object to being given their pre-negotiated cut "plus this flawless ruby, my lord, given freely and in excess of our other contributions." PCs get ennobled, politics is explained, plots are hatched, siblings rise against parents, barons rise against barons, rumours of wars to come spread through the land, etc. It all seems to work fairly well.

I wish I could take that caption back, haha, I had been trying to exaggerate for comedic effect but it doesn't seem to have landed. My brain just runs on rules that are much lighter is all.

DeleteHaha, no worries, took it as such. :D

DeleteGreat post! I was just blogging about this very thing myself as I gear up for a new campaign. Systems have a distinct effect on the game-feel of a campaign.

ReplyDeletehttps://dungeonmusing.blogspot.com/2020/12/rpg-systems-vs-stories-we-tell.html

I've been trying to write a game that tightly integrates setting and rules, so that the experiences defining a character's capabilities also tie the character into the history of the setting. It's very much not Conan or medieval, but instead is a kind of low-Renaissance / colonial steampunk set in an ersatz Central Asian city. There's a lot of bureaucracy and negotiation in the setting, so much more roleplay than roll-play. Some of the character occupations would give advantage / social leverage in roleplay situations.

ReplyDelete