RPGs and Creative Constraints: What’s behind the OSR and FKR?

I.

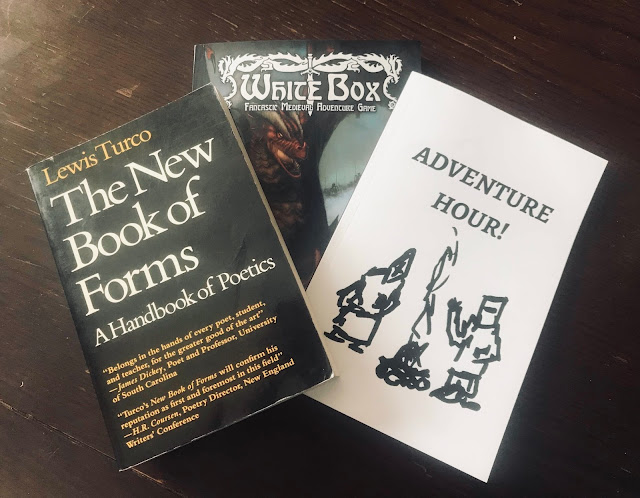

Before RPG design became my main hobby, I used to write poetry. My favorite book on my shelf from that time is The New Book of Forms by Lewis Turco. It explains the fundamental building blocks of poetry (such as what “iambic pentameter” means) and lists, in encyclopedic fashion, all the notable forms within English poetry.

Most modern poetry is free verse, including all the poetry I ever wrote. You put the words together however you think they sound good. There are certain principles to absorb that’ll help you with that, but it’s ultimately up to your intuition of what feels right.

It wasn’t always that way. For various historical reasons — because poetry used to be primarily for performance, because it used to be set to music, etc. — poems almost were almost always composed within a particular form, such as the sonnet or the villanelle.

To gloss over a lot of history: at a certain point, there was a shift. Poets like Walt Whitman popularized a transition to free verse as the dominant form (or lack thereof).

But forms are by no means dead and gone, and I’ve always wanted to try my hand at writing within them. There’s something compelling about introducing a constraint — about taking the wide-open blank page and reducing it a narrow channel within which the words can flow.

II.

I think maybe I’ve been looking at RPGs backwards.

It’s easy to think that the “natural state” of the RPG is to have lots of rules, and running ultralight games with an FKR approach is a divergence from that state. That’s certainly how they emerged historically — the dominant trend after D&D in ‘74 was to write more and more rules that simulated or standardized more and more things. (One could say the same of wargames: there was Kriegsspiel before there was Free Kriegsspiel.)

Free verse was once seen that way. Now, poetic forms are seen as a constraint the poet brings to the blank page to shape their results. Some poets thrive within those constraints; others find them too limiting and cast them off.

What if we look at RPGs this way? What if we view the “natural state” of the RPG as boundless play-pretend, and everything else as a creative constraint?

What might the “New Book of Forms” for RPGs look like?

III.

Imagine you are starting a new campaign, not with a system in mind, but “from scratch.” All you know is that you want to play pretend with your friends.

I think there’s one fundamental characteristic of play-pretend, and it’s this:

- Cause and effect. We all know that some crazy out-of-nowhere things can happen when kids play pretend, but if there isn’t at least a little “yes-and” or “because of that” or “but,” it’s not play-pretend — you’re just talking nonsense.

Maybe cause-and-effect is all you need to get going. More power to you! But, chances are, you’re going to introduce at least one or two of the following constraints.

- The GM/player split. We tend to think of GMless games as an outlier, but play-pretend doesn’t have a GM. I think the referee was the killer innovation behind D&D that led to the explosion of RPGs in the 70s; people went all over the place with their interpretations and rewritings of the rules, but the Dungeon Master was always there at the foundation. Nowadays, some people find this constraint to be more of a limit on their creativity than a boon to it, so they cast it off (a running theme with this entire list).

- Genre or setting. With this constraint, you can no longer introduce just anything that comes to your imagination into the game. It has to match a certain tone, or be in keeping with a certain genre, or make sense given the history of a (usually fictional) place.

- Rules. There is an incredible amount of variation here, because you can design rules to give structure to anything you want, anywhere you want it, and at any level of complexity. Anyone might find any given rule to be the perfect channel for their creativity (like a good poetic form) or an unnecessary limit upon it. This and the wide variety of creative aims in the hobby account for the staggering number of distinct RPG systems that have emerged in just the past 50 years.

- Materials. This is probably a sub-point under rules, but it feels distinct enough that I’m making it a separate point. A game might require d6s, or standard RPG dice, or nonstandard dice, or playing cards or Jenga or whatever else for resolution. Some might assume the use of miniature figures and terrain for combat. It is easy to see how these can be expensive and unhelpful limits, but how they can also add to the experience.

- Prepared content. Adventure modules are the main thing under this category, but random tables belong here too. The story game crowd seems to have largely cast this off as an unnecessary limitation on the game, not to mention the GM's time and energy.

- Safety tools. I don't think safety tools are nearly as constraining as anything else on this list, but they are creative constraints, so they belong here.

These are the building blocks of different "forms" of RPGs — the different stress and rhyme and line patterns. You don't strictly need any of them, but, much like poets who write free verse, you'll probably find you want to keep some in your tool belt.

IV.

I think there's one more type of constraint, but it's more nebulous. It's important, though, because I think it gets to the heart of what the "OSR" really is. I'm going to call it an "approach."

In the beginning, there was the "Old School Primer" by Matt Finch. More recently, there was the "Principia Apocrypha" by David Perry. Both contain a lot of advice for running the game. What does it all boil down to?

In his seminal post, "The Six Cultures of Play," Retired Adventurer argued that the core obsession of the OSR is "player agency." I'm going to push back on that a little. I think the core obsession is the concept of "authentic challenge."

There are two parts to that:

- The game should consist of challenges. The player's skills should be tested (usually, problem-solving skills). There should be an approximation of "winning and losing," or at least the possibilities of success and failure.

- The challenges should be authentic. Victory should not be given to the players; the GM should not "go easy" or pull punches.

What does it mean to pull a punch? To contradict something that has been established (whether known or unbeknownst to the players) in order to make a challenge easier.

I've come to think of this as the "OSR non-contradiction clause." Established things that you shouldn't contradict include many of the building blocks above: don't contradict the world (genre or setting), the rules, die rolls (materials) or the prepared adventure.

I think this concept of authenticity — "don't go easy, don't pull punches, don't contradict" — is the hidden foundation behind almost every idea in the OSR.

Let's look at the advice headers in just the first chapter of the Principia Apocrypha, "Be an Impartial Arbiter":

- Rulings Over Rules, Uphold Logic. Don't contradict the logic of the fictional world. (Note that it also says to apply rulings consistently — the tension between "don't contradict the rules" and "don't contradict the logic of the world" will be important later.)

- Divest Yourself Of Their Fate, Embrace Chaos. Don't go easy on the players (but don't antogonize them either) and don't contradict the dice.

- Leave Preparation Flexible, Build Responsive Situations, Let Them Off The Rails. Linear adventures frequently create dead-end situations that encourage the GM to contradict the adventure or the dice in order to move the PCs along in the plot. So, don't use linear adventures.

This is the "OSR" or "authentic challenge" approach. It is a creative constraint upon your game just like the rules are a constraint upon your game, but it's more of a set of principles.

The willing adoption of this constraint by a sizeable subculture in the hobby has baffled and continues to baffle a lot of people. "Why can't I contradict my prep or the dice if they feel wrong for the experience I'm trying to create? Why do I need to prep anything at all? This sucks."

There's nothing wrong with you if you think that. A valuable creative constraint for some is a needless limitation on others. That's the whole point of this post, if that wasn't clear by now.

But, if you're sitting here wondering what value this approach does provide for many players and GMs, I can point to a couple things:

- "Authentic" challenges provide players with a genuine sense of accomplishment. They know that solving that puzzle or beating that monster was something they earned, not something guaranteed by the GM intervening on their behalf.

- The approach takes a lot of pressure off the GM while they're running. It's no longer your job to mind the pacing of the game or to modify things on the fly to improve the experience. Just follow your prep and what the dice tell you, nice and easy.

V.

With all that established, I think we're in a good position to answer the perennial question: "What the hell is this FKR thing I've been hearing about?"

I think the whole movement stems from a particular frustration with the OSR non-contradiction clause.

Imagine a rule that says a PC can't move in combat after taking their action for the round. A bunch of monsters are about to gobble up this PC because they just used their action to tie their shoe. It doesn't make sense to me, given common sense and the logic of the world, why the PC couldn't just run away.

Do I put "rulings over rules" and allow the PC to run away? Or would that be contradicting the established rules, pulling a punch, going easy?

That's a small, silly example, but over time these sorts of situations add up and create frustration. So, the FKR comes about and experiments with limiting rules.

Maybe they just hide the rules from the players so the players won't see those moments where contradicting a rule could be seen as "going easy." Maybe they run the same rules as they always did, but make it very clear that GM rulings trump rules such that it becomes almost a rule in and of itself.

Or, maybe they just get rid of a lot of rules. Because you don't strictly need them. They're just a constraint upon play-pretend.

Even when it doesn't have rules or dice, though, the FKR still tends to work with a lot of constraints: the GM/player split, genre or setting, prepared content, the occasional safety tools, and all the constraints that come with the authentic-challenge approach.

It's just that these constraints aren't always obvious to us, because we still see our equivalent of poetic forms, rather than free verse, as the default.

|

| From Electric Bastionland, art by Alec Sorensen. |

Joesky Tax: O.S. Prime (a Structural Machine for Electric Bastionland)

15 STR, 7 HP, miniature missile launcher (d8 Blast damage).

- Captures wanderers in the Underground and forces them to undergo a number of challenges or "games" with the promise of treasure as a reward.

- Insists that its rulings are final; responds to any complaint with a rant against "game balance"; blames the PCs' lack of "player skill."

- Lair is surrounded by realistic "ice sculptures." If you look straight into its mechanical eye, O.S. Prime will blast you with a freezing ray (d20 DEX loss) and chastise you for not knowing better.

.jpg)

I think you hit the nail on the head when it comes to forms and RPGs. You want a certain outcome, so you limit the inputs. To want one thing is to reject (but not disrespect) others.

ReplyDeleteArrived at this post via Glatisant, and I feel like I ought to get it tattooed on me somewhere. It addresses, with such clarity, almost all of the major dichotomies that have been nagging at me since I rejoined the hobby 2 years ago: constraints/freedom, dice/improv, GM/GMless, playing/winning. Plus bonus points for the poetry framing, and for pointing out the similarities between childsplay and RPGs, something I think about often.

ReplyDeleteYou also reminded me that a couple of days ago I thought of writing a poem to articulate what bugs me about most naive poetry. And so I did:

When people write a poem for the first time

They always seem to think that the most important thing about a poem is that it should rhyme

For me their lack of rhythm jars, and makes the resulting poem a bit of a hash

Unless you're Ogden Nash

Thanks for this, it really resonated as a circumspect take on similar things I've been reading and thinking.

ReplyDeleteI'd like to raise another boon granted by authenticity: Personalisation of the experience itself. If you play in an old school dungeoncrawl session, you can be pretty sure that the experience your table had would have been different on a different night with anyone else sitting there (exploring different areas, finding different secrets, different random encounters, different outcomes even for the same encounters). In contrast, playing through a modern D&D adventure, you're guaranteed virtually the same experience as any other group, because the experience is the focus, and everything bends to fit it - you're not handed anything at the end that feels like it was personal to you and your group.