The Four Channels of Creative Constraints on RPGs

I’ve come up with what I think is an interesting and useful way of thinking about RPGs, but the seeds of it were planted in my head by an unlikely source.

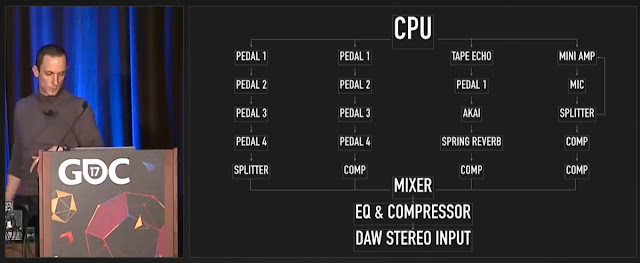

I was watching this GDC talk by Mick Gordon about how he created the music for Doom (2016). In it, he describes how his main instrument for the game was a simple sine wave — what he describes as the purest form of sound — filtered through four channels of machines that distort the “pure” sound into something industrial, noisy, and full of character.

In a previous post, I described all RPGs as the product of different kinds of “creative constraints” upon play-pretend, which you might call the “purest form” of RPG. I listed various kinds of constraints, but this GDC talk made me think — what if I reorganized those constraints into four channels of distortion? Four channels through which you distort and shape the raw energy of play-pretend into something with a particular character?

It turns out it maps pretty well to four channels. So well that I can see myself thinking about RPGs in terms of these channels for a long time. They even have a nice rhythm to them:

Context, Rules, Content, and Principles.

I. Context

I wrote about this channel some time ago in “Why do we all have different preferences in RPGs?” The meat of that post is an argument that we ought to take context more seriously. Context is about questions like…

- How many players are there?

- Are you playing-by-post? In-person? Over voice chat?

- Is the game a dedicated table or an open table?

- How often are you meeting to play? How often are you writing PBP messages?

- Who are the players, anyway? What’s their background, what are their influences? What’s going on in their lives outside of the game and in the world around them?

Context has a great deal of impact on one’s preferences for rules, content, and principles. A complex ruleset like Pathfinder 2E isn’t going to work well over play-by-post. The more arcane rules and principles behind early D&D are baffling to so many people today because they don’t see the open-table context for which they were written.

But context is not just a determining factor for what rules/content/principles you prefer. It is an independent channel, and it’s the one that makes everyone’s game unique. Two groups who play the same adventure with the same rules, following the same principles for play, will still wind up with different experiences. You can transfer rules, content, and principles between games, but you can’t transfer context.

II. Rules

This is the easiest channel to work with, because rules have the most clear and visible impact on the games we play. When you change a rule, it’s relatively obvious what that does to the game and how it reshapes play. There’s a reason we commonly refer to different groups as playing “the same game” if they’re using the same ruleset.

You can’t change your context without finding a new group. You can’t change the principles with which you approach the game without doing a lot of research, (un)learning, and introspection. You can change the content of the game, but that can be a lot of work for little reward — there’s a reason there are more rules-hackers in the world than there are adventure-writers.

You can do a lot of crazy things with rules. You can define what each player controls (a well-defined character? a troupe of flat characters? a loosely-defined head of an organization?) and whether there’s a GM arbitrating things. You can introduce all kinds of materials like dice or cards or Jenga towers or mobile apps. You can create procedures that shape whole sections of the game (‘crawl procedures, different kinds of “scene,” etc.).

But, since it’s so common to view rules as the only differentiating factor between games, I feel obligated to note that rules aren’t all-powerful. There’s a lot that you can’t change with rules unless you make an effort to work with the other four channels.

III. Content

Content is everything you prep before the game. A setting, an adventure, that sort of thing. I probably don’t need to clarify that running a different adventure with the same rules, group, and principles for play creates a different experience — people do it all the time. Eventually, the current adventure ends and you need to run a new one.

A lot of story-game design seems to be about eliminating the need for this channel by folding improvisational prompts into the rules. Meanwhile, D&D 5E provides poor tools for DMs to make their own adventures and therefore seems to assume the use of published adventures. OSR types seem to increasingly run published dungeons/adventures — which are increasingly dressed up in shiny books with trendy layout — rather than create their own.

Everyone seems to want to sidestep the problem of content. It requires a lot of artistic/aesthetic thinking, not just game-design thinking. It’s a ton of work for something each group of players can only experience once, and most GMs only have one group of players.

But genre and setting, the kinds of characters the players encounter, the kinds of narratives and the shapes of spaces they explore — all these are massive elements that make the experience into what it is. It’s a shame that so often we either leave it to someone else or improvise it instead of taking time to really develop it ourselves.

I don’t mean to judge. I know lots of people play in a context that makes doing lots of prep impractical. I just wish we all had the free time to really go wild with developing and refining our content.

IV. Principles

This is what I called an “approach” in the last post, but I think “principles” might be a better fit. Here’s a scattered selection of principles:

- Be a fan of the player-characters.

- The rules-as-written/intended are the highest authority.

- Play to find out what happens.

- Maintaining dramatic tension is more important than fidelity to rules or dice rolls.

- When in doubt, provide players with more information then you think they ought to have.

- You cannot have a meaningful campaign if strict time records are not kept.

- Common-sense, fiction-first rulings trump the rules.

- Divest yourself of the PCs’ fate. Let them die.

- Prep situations, not plots.

You probably got some whiplash from reading all those back-to-back, huh? If you’ve been around different RPG spaces, you can probably discern the different places I pulled those from.

On the recommendation of Lich Van Winkle, I’ve been reading Uncertainty by Greg Costikyan (the designer of Paranoia, Toon, and WEG Star Wars). In Chapter 2 of the book, Costikyan defines games in a way I’ve never seen games defined before: as culturally complex play.

He writes, “In a sense, ‘game’ is merely the term we apply to a particular kind of play: play that has gone beyond the simple, and has been complexified and refined by human culture. Just as novels and movies are artistic forms that derive from the human impulse to tell stories, and music is the artistic form that derives from our pleasure in sound, so ‘the game’ is the artistic form that derives from our impulse to play.”

I think it’s difficult to overstate the impact that culture, from which principles are derived, has on play. There is no “innocent” GM advice, so to speak. Every time a new GM starts scouring the internet to learn how to run the game, they are self-selecting and absorbing an entire culture of play, and those principles come to define their game just as much as anything else.

Developing new principles — shaking up not just the rules of the game, but the way you approach the game itself — isn’t something that a lone individual does very often. It’s theoretically possible, but principles are such an ingrained thing: a real body of knowledge of experience, like a kind of muscle-memory. It typically takes shifts in entire cultures of play, which develop historically over a number of years, to develop new principles.

You can, however, adopt the principles of another subculture of the hobby. You can learn to approach different games with different kinds of principles in order to broaden the kinds of experiences you can have.

Conclusion

I hope that this post will inspire people to think of their games holistically. Your game is not just defined by its rules: it is also defined by who the players are and how they play, the content of the game, and the subcultural principles and assumptions with which the players approach the game.

If you want to play a different kind of game, if you want to have new and broader experiences in RPGs, don’t just change the rules! Experiment with changing all those things!

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment